This article was originally published on Ridgeway Information’s blog in 2019.

Over the course of June 2019, both the Ethiopian and Sudanese people have experienced widespread internet blackouts. However, the neighbouring countries experienced two very different types of internet blackouts for quite different purposes.

In Sudan, the military regime was able to restrict private internet access by disrupting carrier-grade networks. By only attacking the ‘edge’ of the internet, the regime ensured that security services could remain online while protesters had no access. Meanwhile in Ethiopia, the state is reported to have caused two almost total internet blackouts in June in response to an attempted coup and as a measure to stop school exam cheating.

Sudan: Attacking the Edge of the Internet

Sudan has a long history of internet interference and during the popular protest movement against dictator Omar al-Bashir in 2019, the Sudanese regime often restricted online access. In April 2019, Omar al-Bashir’s regime collapsed in the face of a widespread popular uprising. Since then there has been a major confrontation between protestors and the military, who have seized control of the country.

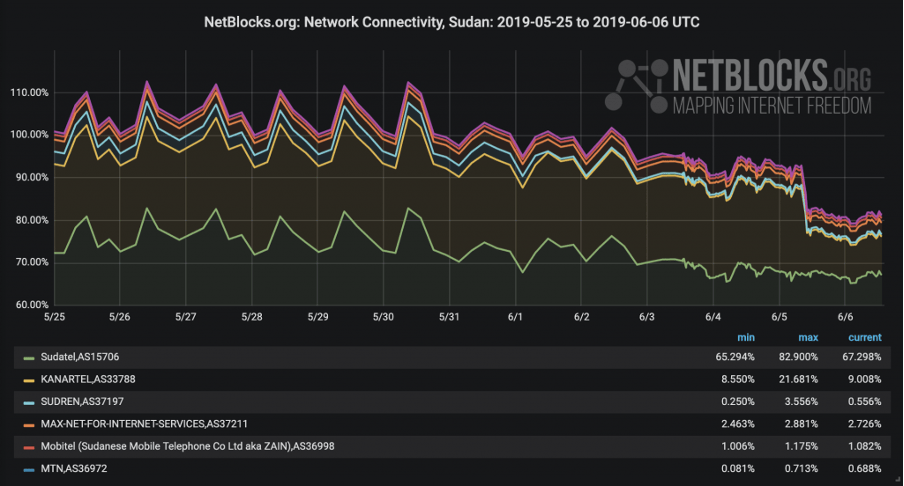

On 3 June a partial internet blackout spread across Sudan with mobile access being particularly affected. While specific providers, such as MTN and Mobitel (Zain) were restricted, internet users could still access fixed-line networks run by Sudatel and Canar. The partial blackout was in response to the failed negotiations between the military and the protestors, however it also occurred on the same day that the military raided a Khartoum sit-in, reportedly with shots fired.

Two days later on 5 June, the internet blackout was extended to affect Sudan’s fixed-line connectivity as well as mobile accessed internet. Once again the blackout accompanied violence. A paramilitary group killed over 100 sit-in demonstrators in Khartoum. By 10 June, the last remaining internet provider Sudatel was disrupted with the army accepting responsibility for the blackout.

Attacking the edge of the internet

The Sudanese military caused a very specific type of internet blackout. For a start, research from Net Blocks show that nationwide IP connectivity only fell to 80%. Yet, the 20% targeted by the military held within it the gateways for carrier-grade network (CGNAT) routes that connect the majority of Sudan’s citizens.

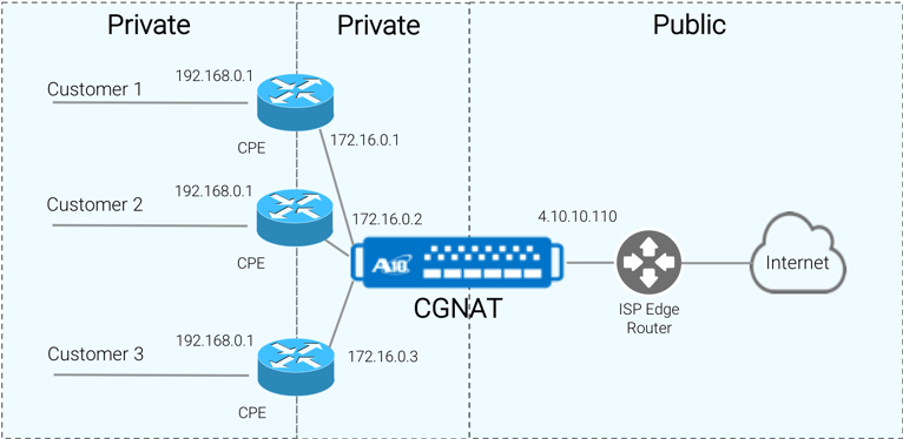

CGNATs allow internet providers to bunch together private internet users under a single public IP address. What this means in this context is that by disrupting CGNAT routes, the military was able to efficiently restrict internet access to private customers without disrupting the core Sudanese internet infrastructure.

By maintaining the core internet infrastructure, the Sudanese military is likely to have kept continued internet access for security workers and state officials. Thus, by attacking the edge networks and disrupting CGNAT routes, the Sudanese military not only disrupted the organisation of protests and the flow of information out of the country, but they give security forces an advantage by keeping them online.

Ethiopia: A Failed Coup & Exam Cheating

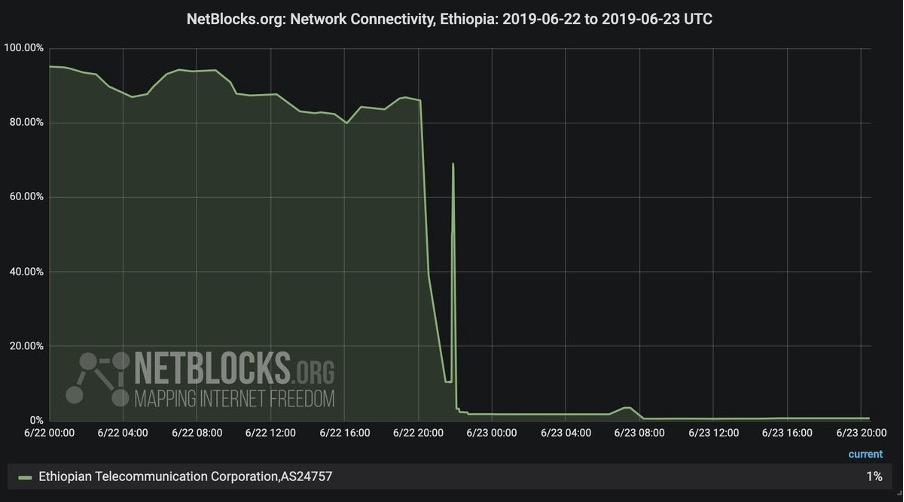

Violence erupted in Amhara state, in northern Ethiopia on 22 June. The Amhara State President and the Army’s chief of staff were assassinated in two separate attacks. Reports suggest that this was an attempted coup led by General Asamnew Tsige who was recently released from prison after serving time for a similar coup attempt.

On the same day as the coup the internet was largely disconnected in Ethiopia. In contrast to Sudan, network data in Ethiopia dropped to 2% of its normal use. The blackout began in northern Ethiopia and spread to the eastern regions before eventually disconnecting the whole of the country. Because Ethiopia only has one internet provider, which is state run, it is far easier for the government to completely disconnect the country. According to NetBlocks, the remaining 2% connectivity may belong to officials in the capital as well as tourist locations.

Leave a comment